BERNIE VAATSTRA

A 12-year-old female neutered Domestic Short-hair cat developed a raised, crusted, circular lesion on the right upper lip. The lesion was pruritic and did not respond to treatment with glucocorticoids.

An incisional biopsy was submitted for histopathology.

Histopathology findings:

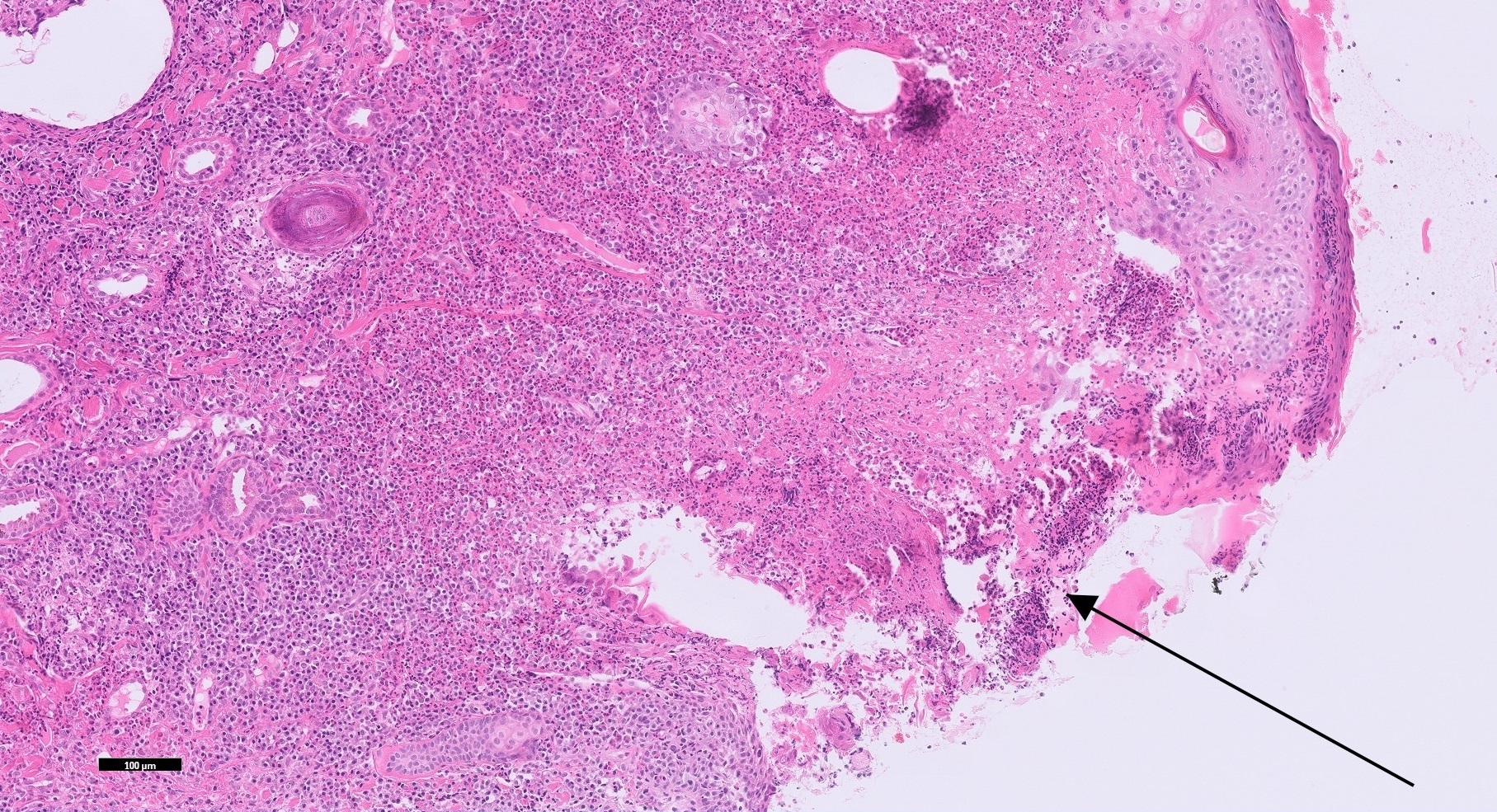

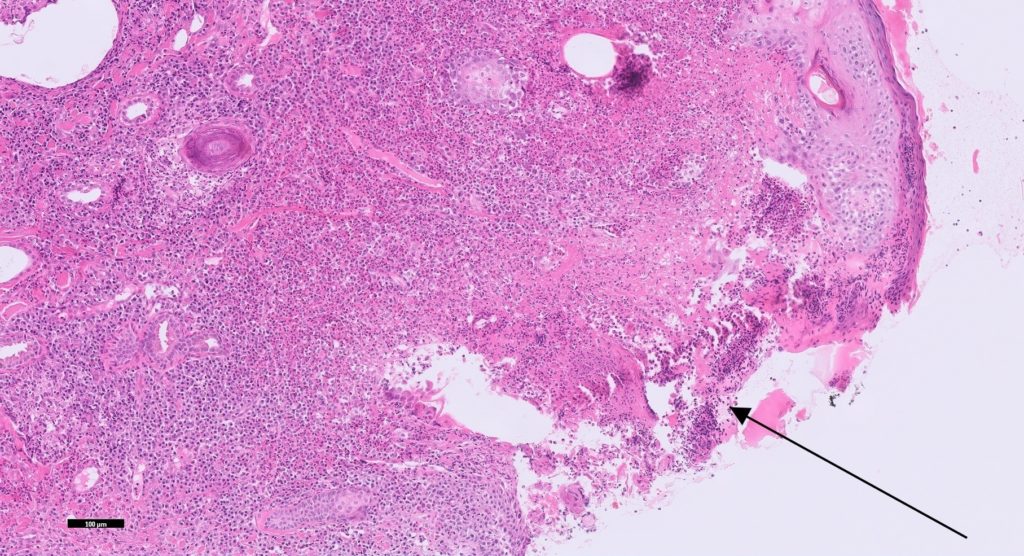

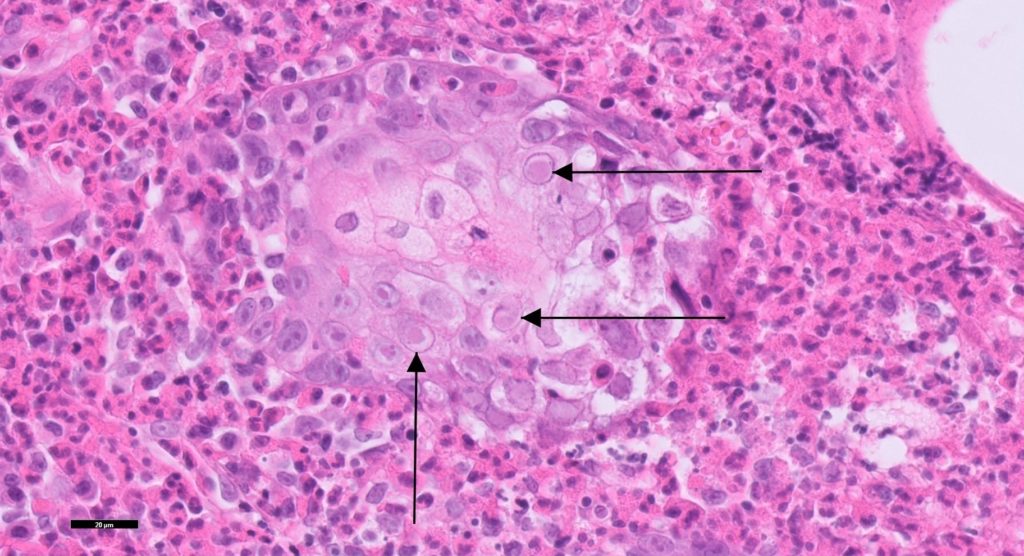

The epidermis was focally ulcerated and crusted (Figure 1). The dermis was infiltrated by large numbers of mixed inflammatory cells including many eosinophils. Follicles were often disrupted by inflammation. Small numbers of swollen sebocytes and keratinocytes contained eosinophilic intranuclear inclusions which marginated the chromatin (Figure 2.). The final diagnosis was feline herpesvirus dermatitis.

Discussion:

Feline herpesvirus-1 is a very common cause of upper respiratory disease in cats. Clinical signs include sneezing, fever, anorexia, conjunctivitis, and serous nasal and ocular discharge. In addition corneal, oral, and cutaneous ulceration may occur in severely affected cats. It is estimated that 80% of recovered cats are latently infected carriers. Relapse may occur with stress or glucocorticoid therapy.

Feline herpesvirus dermatitis affects adults more commonly than kittens and may develop with or without concurrent respiratory signs. Ulcerated and crusted lesions characteristically involve the nasal planum although similar lesions may occur elsewhere, e.g. lips, ears, periocular skin, and paws.

Clinical differentials for herpesvirus dermatitis include mosquito hypersensitivity, eosinophilic granuloma and plaque, pemphigus foliaceus, FeLV dermatitis, calicivirus dermatitis, and actinic keratosis. Concurrent respiratory signs and adverse response to glucocorticoids aid the diagnosis.

Biopsy is useful but not always definitive since viral inclusion-bodies are not detected at all stages of infection. PCR testing of a fresh skin biopsy or swab from affected skin can confirm the presence of FHV-1, noting that false positives are possible with contact with nasal or conjunctival mucosa or secretions.

Treatment options include topical and systemic antivirals, lysine supplementation, and correction of any underlying causes of stress or immunosuppression (e.g. concurrent disease, glucocorticoid therapy). Vaccination helps protect against clinical disease but does not completely prevent infections or the development of carrier state.

Thank you to Jo Lin Chia of Lynfield Vets for submitting this interesting case.

Reference: Miller WH, Griffin CE, Campbell KL. Viral, Rickettsial, and Protozoal Skin Diseases. In: Muller and Kirk’s Small Animal Dermatology, pp 347-8, Elsevier, St Louis, 2013