– Indications, techniques and benefits

Bernie Vaatstra

Liver disease is very common in dogs and cats and frequently presents a diagnostic challenge. A survey of 1,725 cat veterinary visits found a prevalence of liver disease or about 7% diagnosed through laboratory and imaging studies (Melchert et al, 2016). A post-mortem survey of 200 unselected dogs from first opinion practice found a 12% prevalence of chronic hepatitis, suggesting overall liver disease prevalence is even higher (Watson et al, 2010).

Liver disease may be primary or develop secondary to systemic disorders (e.g. endocrinopathy, GI and pancreatic disease). Primary liver disorders are broadly classified by the WSAVA as vascular, biliary, parenchymal, or neoplastic (Rothuizen et al, 2006). Some animals have multiple overlapping processes.

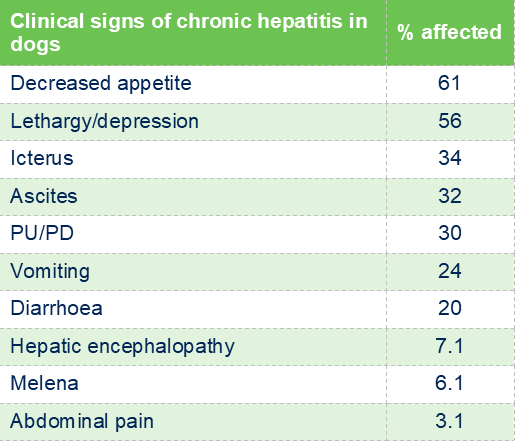

Given the multiplicity of metabolic and immunological functions performed by the liver, disease may induce a wide range of non-specific clinical manifestations. See Table 1.

Diagnosis of liver disease therefore relies on synthesis of a range of clinicopathological findings – clinical signs, serum biochemistry (liver enzymes, function tests, pancreatic lipase, and serum proteins), tests for infectious agents (e.g. Leptospira serology/PCR, Toxoplasma and Neospora serology, bacterial cultures), imaging, fine needle aspirate, and biopsy. While all these techniques have their advantages and limitations, biopsy remains the gold standard for accurate diagnosis.

However, information gleaned from a biopsy depends heavily on appropriate case selection, careful technique, and adequate sample handling and preparation.

Liver biopsy indications

Indications for liver biopsies in companion animals include the following (Unterer 2017):

1. Persistent elevation in liver enzymes (serum ALT, AST, and ALP)

2. Abnormal liver function tests (serum bile acids, albumin, bilirubin, BUN, cholesterol, glucose)

3. Imaging evidence of structural liver disease including masses

4. Breed associated liver diseases

Prior to biopsy, non-hepatic causes of liver enzyme increases should be excluded. In addition, infections such as leptospirosis and FIP should be ruled out. Risk of haemorrhage also needs to be considered. A study of dogs undergoing percutaneous ultrasound guided liver biopsy reported a high incidence (42.5%) of clinically silent, major haemorrhage, but few complications (1.9%). While it has been historically advised to assess haemostasis parameters prior to liver biopsy, the same study showed no correlation between mild abnormalities in haemostasis as detectable by routine tests (PT, APTT, platelets) and risk of post-biopsy haemorrhage (Reece et al, 2020). Ultimately, the decision to biopsy is a clinical one weighing up the risks and benefits.

Liver biopsy technique

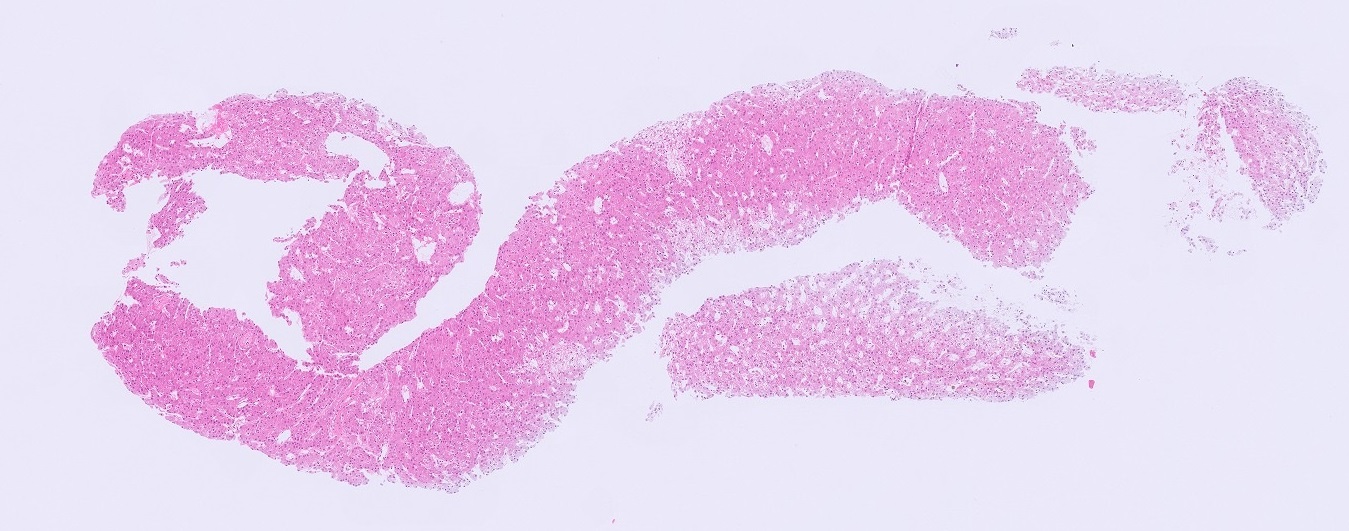

In order to accurately evaluate all compartments of the liver (hepatocellular, biliary, vascular, interstitium), samples need to include enough architecture. Ideally, 12-15 portal tracts should be examined to have confidence in diagnosing or excluding lesions of the biliary tree and vasculature (see Figure 1). Practically, this usually means submitting three biopsies from different lobes. Avoid the quadrate lobe (adjacent the gallbladder) due to the presence of artefact. Avoid the caudate lobes if assessing for vascular anomalies such as portal vein hypoperfusion. This leaves the left and right medial and lateral lobes as the best locations to sample, unless targeting a focal lesion.

Studies have shown that surgical wedge biopsies are the best for diagnosis of liver diseases. However, given the morbidity involved in this procedure, ultrasound guided percutaneous needle/trucut biopsies (14g for larger dogs, 16g or 18g for smaller dogs and cats), punch biopsies (8mm) and laparoscopic cup (5mm) biopsies can be used as alternatives. It is important to avoid crush trauma with the cup and punch biopsies in particular. Take into account that the diagnostic accuracy of biopsies obtained by needle, cup or punch ranges from 60-70% when compared with large wedge biopsies (Kemp et al, 2015).

Liver biopsy uses

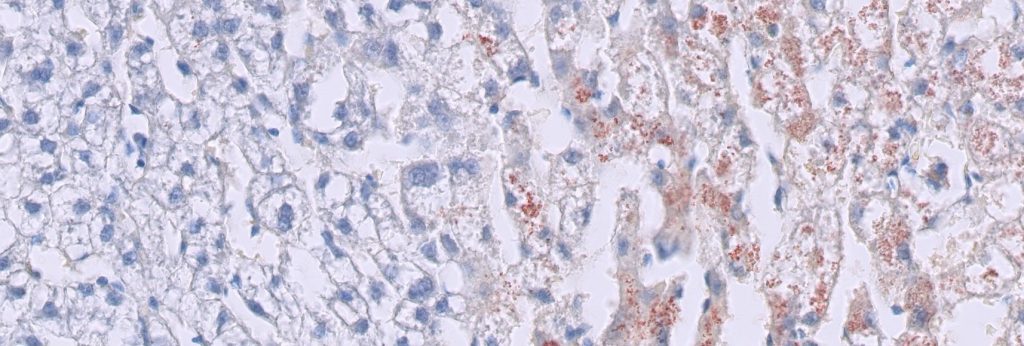

Biopsy helps to categorise the pathology, estimate chronicity, guide management, evaluate progress, and inform prognosis. Targeted histochemical stains can be used for identifying and quantifying fibrosis, assessing architectural collapse or regeneration, estimating copper stores (Figure 2), visualising glycogen or lipid, and identifying microorganisms. In some cases, liver biopsy may only provide a morphological diagnosis and a list of suggested differentials, whereas in others, a more specific aetiological diagnosis is possible.

Scenarios where biopsy is particularly useful, and often essential for diagnosis, include:

· Canine chronic hepatitis vs non-specific reactive hepatitis

· Feline lymphocytic cholangitis vs hepatic lymphoma

· Feline neutrophilic cholangiohepatitis vs lymphocytic cholangitis

· Benign vs malignant neoplasia

· Primary vs metastatic neoplasia

· Glycogen vs lipid vacuolation

· Portal vein hypoperfusion

· Ductal plate malformation

· Copper hepatopathy (in conjunction with liver copper analysis)

· Identification of infectious agents (protozoa, bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi, viral inclusions)

· Toxic hepatopathies

· Chronic passive congestion

· Cirrhosis

· Storage disorders

Limitations

The value of liver biopsy may be limited by factors such as non-representation of multifocal or regional lesions, handling artefact, sampling from inappropriate sites, and the presence of chronic end stage or resolved lesions. Interpretation is always made in light of the clinical picture and, ideally, serial biochemistry, imaging, and function tests.

References

Kemp SD, Zimmerman KL, Panciera DL, Monroe WE, Leib MS, Lanz OI. A comparison of liver sampling techniques in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 29:51-7, 2015

Melchert A, Souza FB, Guimaraes-Okamoto PTC. Prevalence of Liver Disease in Cats from Botucatu City, Sao Paulo State, Brazil. World Small Animal Veterinary Association Congress Proceedings, 2016.

Reece J, Pavlick M, Penninck DG, Webster CRL. Hemorrhage and complications associated with percutaneous ultrasound guided liver biopsy in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 34:2398-2404, 2020.

Rothuizen J, Bunch SE, Charles JA. WSAVA standards for clinical and histological diagnosis of canine and feline liver disease: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2006.