Cristina Gans

Clinical history

A one-year-old DLH cat presented to the veterinarian for acute -onset anorexia and lethargy. Additional findings on clinical examination were a reduced body condition and moderate pyrexia. After treatment with antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, the cat displayed a marked improvement in appetite and demeanour and was discharged from the hospital. Shortly afterwards, the cat developed neurological signs, including ataxia and nystagmus. The cat was rushed to an emergency veterinary hospital but died just prior to arrival.

Gross findings

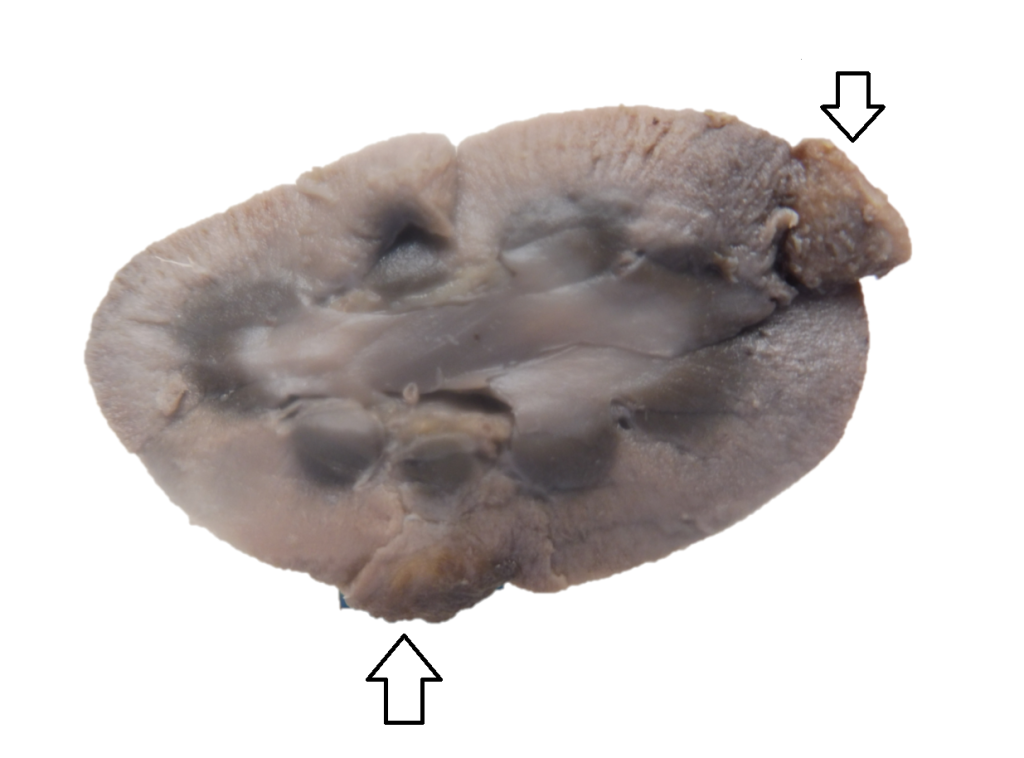

A full necropsy was performed by the referring veterinarian, and lesions were identified in the brain, kidney and liver. A single 10 mm diameter mass was identified in the cerebral cortex, from an area associated with the right temporal and frontal lobes. Two well-demarcated masses (measuring 7 and 11 mm) protruded from the cortex of the right kidney (figure 1). These masses were all described as green and gelatinous by the referring veterinarian, but upon fixation, the colour changed to a dark brown-black pigmentation. A small focal cream-coloured lesion was identified in the right lateral lobe of the liver.

Histological findings

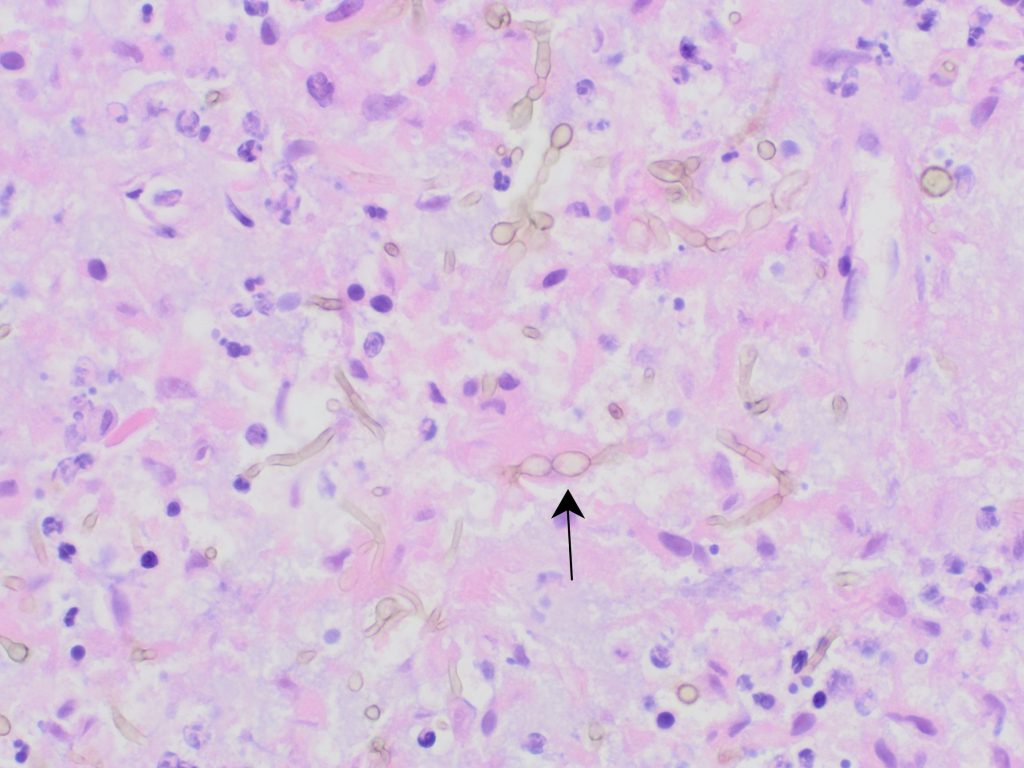

Within the renal cortex of both kidneys and within the cerebral cortex of the brain were multiple foci comprised of central necrosis surrounded by neutrophils and macrophages and further surrounded by fibrosis and granulation tissue. Within necrotic foci were abundant pale brown, septate, branching hyphae with slightly bulbous 3 to 6 μm diameter walls (figure 2). Also present were moderate numbers of 6 to 10 μm diameter ovoid to spherical conidia. Within the brain, neutrophils occasionally infiltrated the walls of blood vessels within the parenchyma, consistent with a vasculitis. Rare fibrin thrombi and rare fungal hyphae were sometimes associated with these vessels. The lesion in the liver corresponded to an area of mixed inflammation, but fungal hyphae were not identified in this lesion.

Diagnosis

Pyogranulomatous and necrotising encephalitis and nephritis within intralesional pigmented fungi, consistent with disseminated phaeohyphomycosis.

Discussion

Fungal encephalitis due to phaeohyphomycosis is a rare presentation in cats, but it has been reported in multiple case reports worldwide, including in Australasia. Other differential diagnoses for infectious causes of encephalitis for NZ cats include feline infectious peritonitis, feline panleukopenia virus, other viral causes (FIV/FeLV/FHV-1), Toxoplasma gondii, Cryptococcus, and bacterial infections. Most infectious causes of CNS disease result in neurological signs that are acute in onset and progressive, with some cases becoming chronic (Gunn-Moore and Reed, 2011).

Phaeohyphomycosis is an umbrella term which includes a number of pigmented dematiaceous fungi including Cladophialophora bantiana (previously known as Cladosporium bantiana). Dematiaceous fungi are mostly soil organisms associated with plant material as plant pathogens. Although infection is uncommon, the most common presentation in cats is the presence of single or multiple cutaneous ulcerated plaques or nodules. Access through broken skin, either directly through trauma or indirectly through contamination of a pre-existing wound is suspected as the primary mode of infection; however oronasal infection has also been suspected. Direct transmission between hosts has not been reported (Lloret et al, 2013).

Systemic dissemination is uncommon, and encephalitis is infrequently reported. Encephalitis in cats is most commonly associated with Cladophialophora bantiana, due to the neurotropic nature of the fungus (Russell et al, 2016; Mariani et al, 2002). Other reported sites include the lungs, nasal cavity, liver and kidneys. CNS infections are thought to occur via the respiratory route, but ocular and aural routes of entry have also been suggested (Bouljihad et al, 2002).

In this case, no gross pulmonary disease or skin wounds were identified and the route of infection was undetermined. Fungal hyphae within rare blood vessels are suggestive of a haematogenous route for the dissemination.

Ancillary diagnostic tests may be helpful in the diagnosis of a fungal encephalitis, but are rarely specific for a particular infectious cause. Serum biochemistry and routine haematology may be supportive of systemic inflammation and lower the clinical suspicion for other causes such as feline infectious peritonitis. Reported findings on CSF analysis may be inconsistent with suppurative or granulomatous pleocytosis and variable increases in protein content present in some, but not all, cases. MRI and/or CT imaging may identify a mass lesion, although the cause of such lesions is rarely specific. Definitive antemortem diagnosis of fungal encephalitis (with the exception of Cryptococcus) is rare. However, in one case report of an adult cat with disseminated lesions in the liver and kidney, pigmented fungi were identified on cytology of masses in the liver and kidney (Cohen and Johnson, 2025).

Most feline cases have not identified any underlying predisposing factors; however, there have been cases associated with corticosteroid administration and lymphocytic leukaemia (Bouljihad et al, 2002). In this case no other systemic disease was identified, and there was no history of corticosteroid administration. The FIV/ FeLV status was unknown for this patient.

Thanks to Nick Page and Rolleston Veterinary Services for submission of this case.

References

Bouljihad M, Lindeman CJ, Hayden DW. Pyogranulomatous meningoencephalitis associated with dematiaceous fungal (Cladophialophora bantiana) infection in a domestic cat. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 14:70-72, 2002.

Cohen J, Johnson K. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis caused by Cladophialophora in an immunosuppressed cat. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound. 66(1), 2025.

Gunn-Moore D A, Reed N. CNS disease in the cat: current knowledge of infectious causes. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 13:824-836, 2011.

Lloret A, Hartmann K, Pennisi MG, Ferrer L, Addie D, Belák S, Horzinek MC, et al. Rare opportunistic mycoses in cats: phaeohyphomycosis and hyalohyphomycosis: ABCD guidelines on prevention and management. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 15:628-630, 2013.

Mariani CL, Platt SR, Scase TJ, Howerth EW, Chrisman CL, Clemmons, RM. Cerebral phaeohyphomycosis caused by Cladosporium spp. in two domestic shorthair cats. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 38:225-230, 2002.

Russell EB, Gunew MN, Dennis MM, Halliday CL. (2016). Cerebral pyogranulomatous encephalitis caused by Cladophialophora bantiana in a 15-week-old domestic shorthair kitten. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery Open Reports. 2(2), 2016.