Cathy Harvey

Clinical history

A six year-old Irish Setter presented at his veterinarian for worsening lethargy, tachypnoea and anorexia. He had been treated with multiple antibiotics over the past several months for a swollen left elbow and lameness. Two days prior to presentation he started drooling excessively, along with heavy breathing. Previous blood work showed a low haematocrit, moderate neutrophilia, severely elevated CRP (>100) and mild hypoalbuminemia. The dog was euthanised and submitted to the laboratory for necropsy.

Post mortem findings

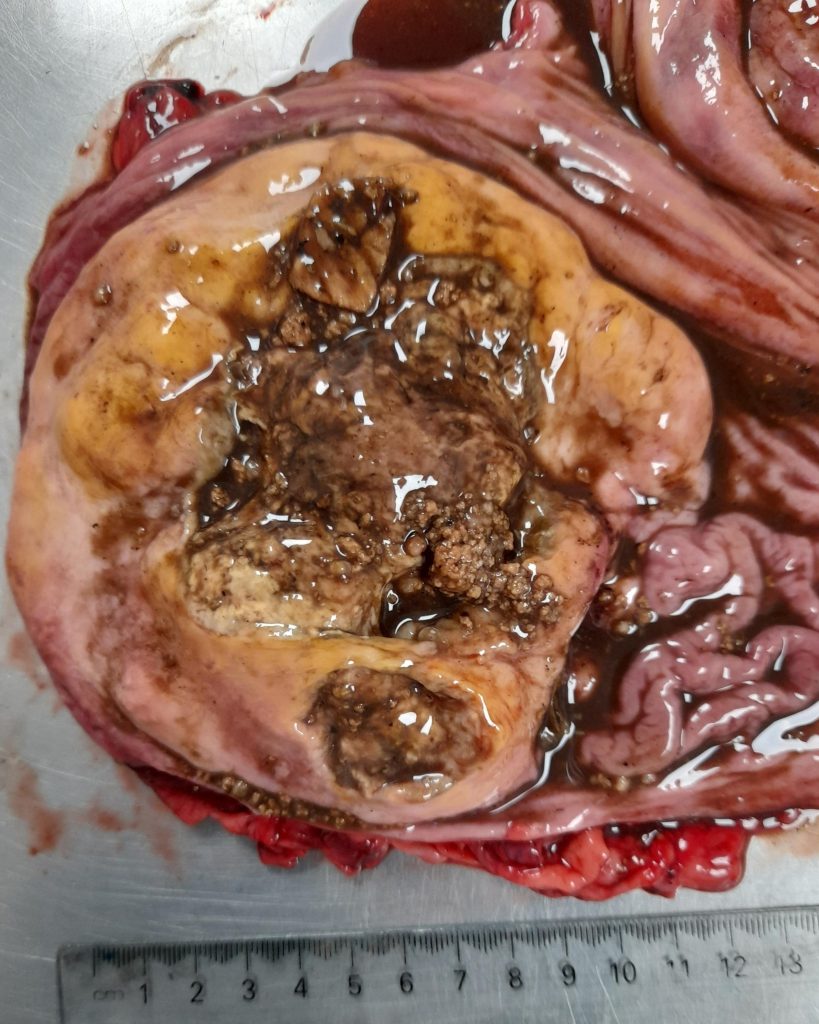

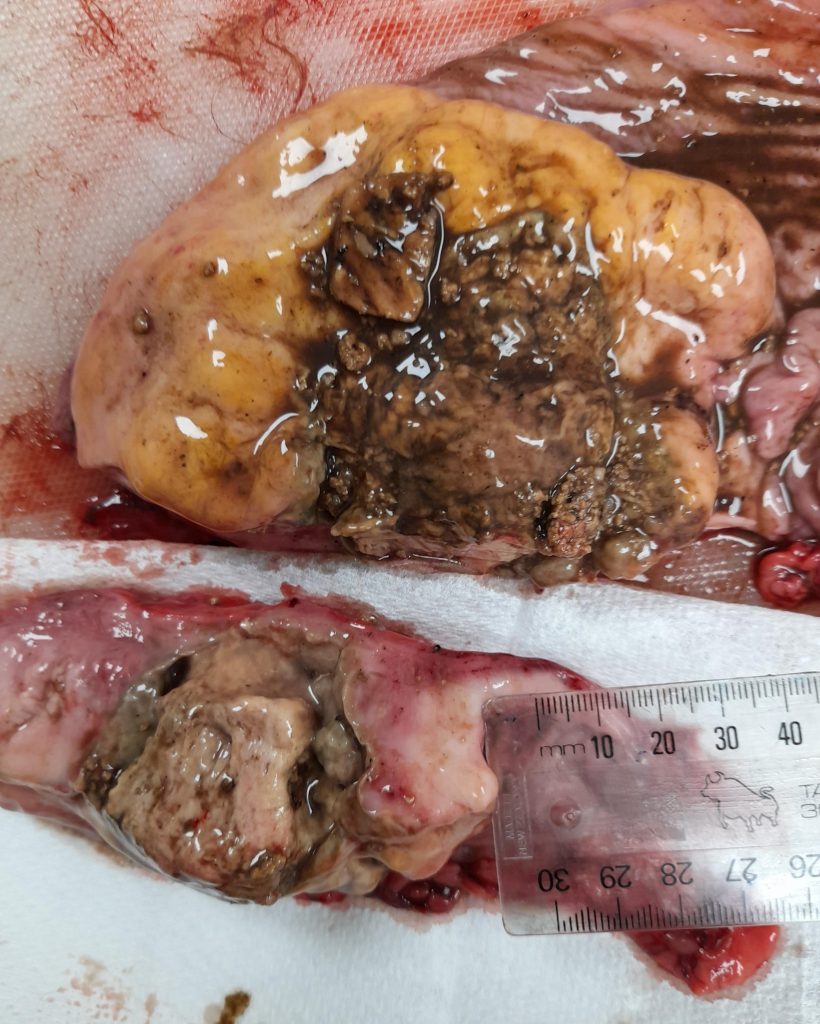

The stomach contained an ulcerated transmural white-tan semisoft mass (figure 1a & b). The adjacent gastric/splenic lymph nodes were markedly enlarged, were diffusely semisoft, red-tan-white with a 15 mm firm brown area. The sternal lymph node was markedly enlarged, soft and diffusely tan-red. Mild pulmonary oedema was evident in the lungs.

Histology findings

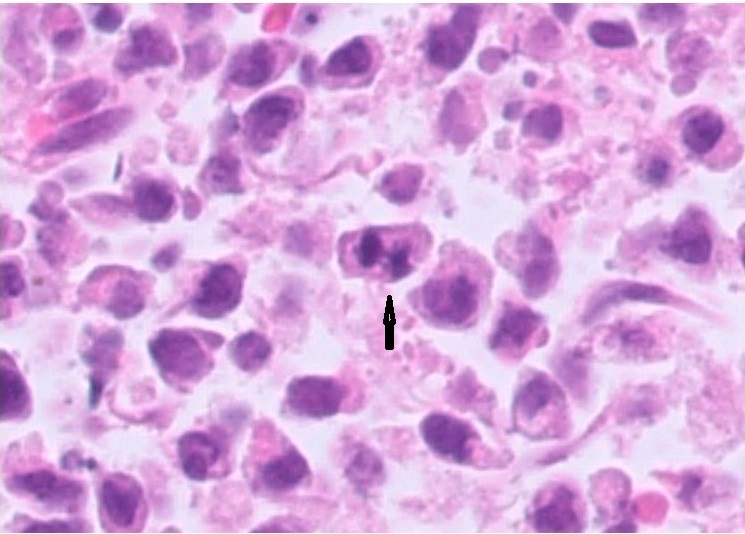

Stomach mass, sternal lymph node, gastric / splenic lymph node and spleen displayed sheets of neoplastic large lymphocytes with numerous mitotic figures (figure 2). The neoplastic lymphocytes had a small to moderate amount of cytoplasm and moderate anisokaryosis of the round to clefted nuclei. The neoplastic cells were transmural in the stomach and extended into the adjacent adipose tissue surrounding the lymph nodes. The stomach was ulcerated, and the lymph nodes contained areas of necrosis. The lungs contained numerous neutrophils and small numbers of mixed bacteria.

Diagnosis

Transmural gastric large cell lymphoma with ulceration, and metastases in gastric/splenic and sternal lymph nodes, with necrosis. Severe neutrophilic bronchopneumonia was also present.

Discussion

Gastric neoplasia is reported to be rare in dogs. In surveys of canine neoplasms, only 0.06% to 0.2% were gastric neoplasms. Around 75% of canine gastric neoplasms are malignant, with adenocarcinomas comprising 60% of all neoplasms. Leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas have been reported to represent 19% and 8% of canine gastric neoplasms, respectively. Lymphoma is the only other type of neoplasm commonly reported in the canine stomach, representing around 9% of neoplasms. The most common clinical signs of gastric neoplasia in dogs are vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss. Less commonly hematemesis, anaemia, melena, diarrhoea, polydipsia, and abdominal pain are observed.

Initial investigation of suspected gastric neoplasia in dogs is often by contrast radiography or ultrasonography. Ultrasonography has been reported to have a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 71% in detecting canine gastric neoplasia and is also useful to guide fine needle aspirates or punch biopsies. Endoscopy can identify some epithelial neoplasms; however, diffuse adenocarcinomas form sessile intramural masses and can be difficult to detect endoscopically. Multiple deep endoscopic biopsies should be taken of ulcerated neoplasms to maximize the chances of obtaining a diagnostic sample. An invasive behaviour of the cells is an important indicator of neoplasia. This can be difficult to assess from an endoscopic biopsy and it may not be possible to make a definitive diagnosis, especially in well differentiated neoplasms.

Cytology may allow a definitive diagnosis of a gastric malignancy. Specimens for cytology can be obtained by endoscopic brush samples, ultrasound guided fine-needle aspirates, or abdominocentesis. As with other ulcerated neoplasms, surface inflammation may prevent diagnosis from an endoscopic brush sample. Furthermore, as diffuse adenocarcinomas are predominantly present in the submucosa, endoscopic brushings may not collect neoplastic cells. Ultrasound guided fine-needle aspirates of gastric neoplasms are useful, although a study of 14 canine and feline gastric neoplasms revealed complete agreement between cytological and histological diagnosis in only half of cases. Cytological differentiation between an adenoma and a hyperplastic polyp and differentiation between a small cell lymphoma and lymphocytic gastritis is not possible. Although abdominal carcinomatosis has been reported in both dogs and cats with gastric neoplasia, abdominocentesis is less commonly used as a diagnostic test in these species.

Gastric lymphoma in dogs usually develops as a component of more extensive intestinal disease. As the mammalian gastrointestinal tract has one of the largest populations of lymphoid cells in the body, it is unsurprising that the gastrointestinal tract is the most common location of extranodal lymphomas in most domestic species. Although a gastrointestinal lymphoma is initially confined to the gastrointestinal tract, it may spread to mesenteric lymph nodes or other tissues as the disease progresses.

Grossly, intestinal lymphoma may be diffuse or localized; when localized, the lesion can bulge intraluminally or be intramural. Neoplasia may be restricted to one site in the intestinal tract, diffusely infiltrate the small or large intestine, or multiple tumours may occur at various levels. Intestinal lymphomas can be plaque-like, nodular, diffuse, or fusiform (circumferential) in shape. Fusiform intramural or transmural lesions frequently balloon outward because the invaded muscle atrophies, leaving proliferations of neoplastic lymphoid cells supported only by parallel bands of delicate reticulum fibres. Advanced, diffuse lesions present as thickened rigid mucosal folds in the stomach, and in intestinal cases the mucosal surface has a granular or cobblestone appearance.

Gastrointestinal lymphoma is much less common than the multicentric form in dogs. However, the gastrointestinal tract is the most common extranodal location for lymphoma in dogs and accounts for 5–7% of all canine lymphomas. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma affects a wide variety of breeds and has a higher prevalence in male dogs. The disease can develop at any age, but old to middle‐aged dogs are most commonly affected (median age around 8 years).

No aetiology has been established. The most common clinical signs include vomiting, diarrhoea, melena, weight loss, anorexia, and lethargy. Non‐regenerative anaemia, neutrophilia, and hypoalbuminemia are common in dogs with gastrointestinal lymphoma. Gastrointestinal lymphomas in dogs occur most commonly in the small intestine, followed by the stomach and the large intestine. In recent studies T‐cell lymphomas are more common than B cell lymphoma. Multifocal tumours, which are less common than single tumours, may involve various combinations of different sites, for example, stomach and small intestine. The prognosis is poor and dogs rarely survive longer than 6 months after diagnosis. There are no outcome data based on prospective studies.

Acknowledgements to Dr Wen-Jie Yang, Veterinary Specialists Aotearoa for this case.

References

> Tumors in Domestic Animals Fifth Edition. Edited by Donald J. Meuten. 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

> Kojima et al. Histopathological features and immunophenotyping of canine transmural gastrointestinal lymphoma using full-thickness biopsy samples. Vet Path. 58:1033-1043, 2021.