KATHRYN JENKINS

Clinical history:

A 3-year-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel presented with a 4-5 week history of respiratory disease. Radiographs demonstrated a diffuse interstitial lung pattern.

Fluid samples from a tracheal wash, material from the endotracheal tube and a FNA from the lung were all submitted for cytologic examination.

Laboratory results:

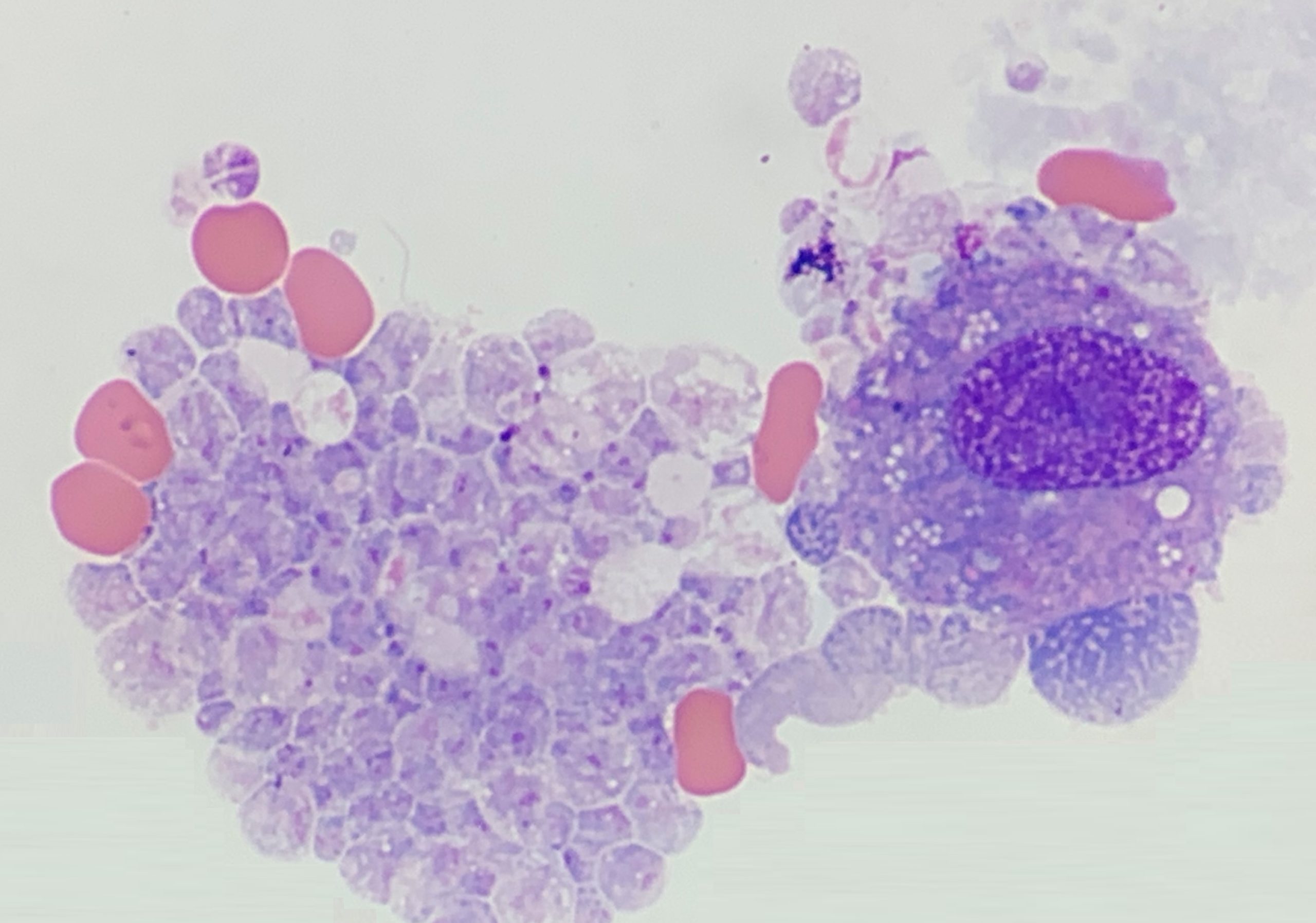

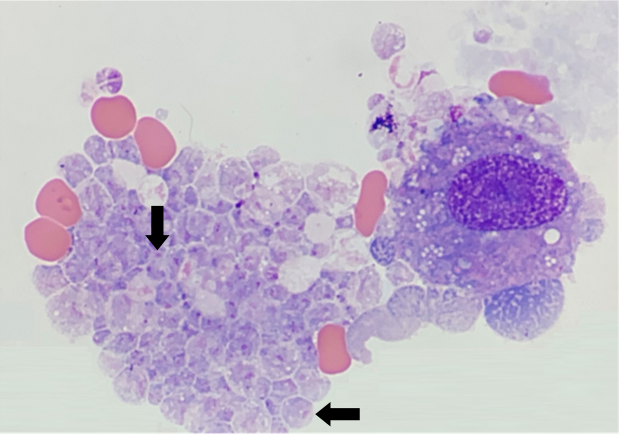

Cytology of the tracheal wash fluid revealed a mixed inflammatory population (mostly foamy macrophages and neutrophils, with fewer mixed lymphocytes), clusters of ciliated respiratory epithelial cells, including increased goblet cells, and frequent often clustered organisms occurring extracellularly and rarely phagocytosed with both neutrophils and macrophages.

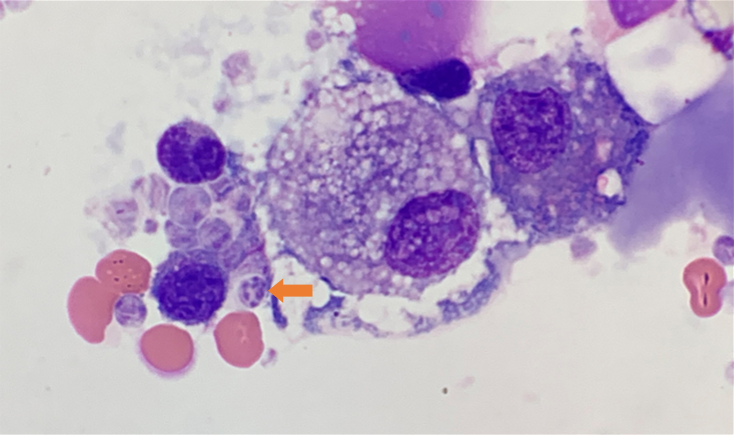

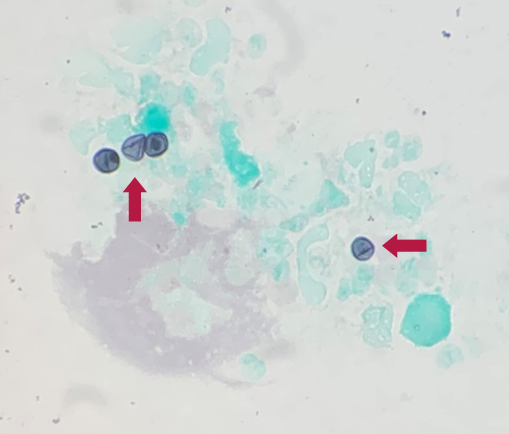

Organisms were round to ovoid, 4-5 μm in diameter, pale blue with a small magenta nucleus (Figure 1). Rarely fewer cystic forms (containing 8 intracystic bodies) were observed (Figure 2). One smear was stained with a special stain (Gomori methenamine silver), which highlighted the organisms with a characteristic ‘crushed ping pong ball’ appearance (Figure 3).

Diagnosis:

The characteristic cytologic findings were consistent with Pneumocystis species.

Discussion:

Pneumocystis sp. are a species specific fungal organism that can act as commensals, opportunists, or pathogens of the respiratory tract, in a wide range of mammalian hosts, including dogs. In cases of immune suppression the organism can become an opportunist pathogen, associated with clinical signs of pneumonia.

In dogs, pneumocystis pneumonia can be a life-threatening disease, with organisms filling alveolar spaces and causing an associated florid inflammatory response within the pulmonary interstitium. Reported disease cases are few in the literature, and prevalence studies in healthy dogs have yet to be performed for this organism (Best, 2019). The majority of cases in dogs have been reported in young adult Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, with smooth and wire-haired Miniature dachshunds also being predisposed. Interestingly, co-existing demodicosis is found in many cases, indicating the potential for immune dysregulation. In dogs, Pneumocystis canis has recently been characterised via molecular techniques.

Diagnosis has traditionally required identification of Pneumocystis ‘cysts’ on bronchoalveolar lavage samples, or transthoracic FNA samples of lung. Freshly prepared smears from fluid or FNA samples are important to be able to identify this organism, as poorly preserved organisms can mimic platelets in the background of the smear. Panfungal PCR and human PCR for Pneumocystis jirovecii do not reliably detect canine Pneumocystis infections. A species specific PCR for dogs has recently been developed for research purposes in Australia (Danesi, 2017).

Early treatment with antibiotics (e.g. trimethoprim-sulphonamide) may be successful in some cases. The patient in this case responded quickly to treatment and went on to a full recovery.

Many thanks to Julia Giles, Totally Vets, Feilding, for this interesting case.

References:

Best MP, Boyd SP, Danesi P. Confirmed case of Pneumocystis pneumonia in a Maltese Terrier × Papillion dog being treated with toceranib phosphate. Australian Veterinary Journal, 97:162-165, 2019.

Danesi P, Ravagnan S, Johnson LR et al. Molecular diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia in dogs. Medical Mycology 55:828-842, 2017.