Sunao Fujita

Clinical history

An 18-month-old, spayed, American Staffordshire Terrier recently presented at the veterinarian for lethargy and inappetence. Pale mucous membranes and pyrexia (39.9°C) were observed on physical examination. In-house CBC and chemistry revealed marked anaemia and mild hyperbilirubinemia, respectively. An EDTA sample was sent to Awanui Veterinary for a full CBC including blood film examination.

Laboratory findings:

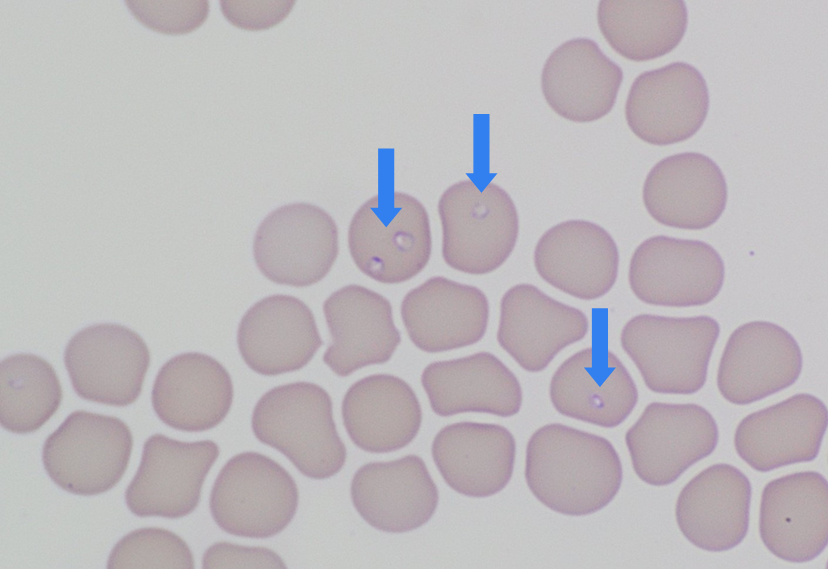

Moderately severe anaemia (HCT 22%, reference 37-55%) with mild regenerative response (reticulocytes 103 x 109/L) and mild neutrophilia (13.1 x 109/L, reference 3.6-11.5 x 109/L) were confirmed. Coombs test was negative with no agglutination on the blood films, suggesting IMHA was unlikely. Platelet counts appeared adequate on the blood films. Moderate numbers of small (1-3 µm) ring-like structures with a thin blue cell membrane, pale cytoplasm and eccentric dot like nucleus were seen in the RBC’s, resembling Babesia piroplasm (small form) (Figure 1).

This case was reported to MPI since Babesia species are exotic and notifiable blood parasites in New Zealand. The EDTA sample was sent to Animal Health Laboratory, Wallaceville and Babesia gibsoni was identified on the molecular testing.

Discussion

This Babesiosis case was recently diagnosed in Canterbury. Babesia gibsoni is a haemotropic protozoa that can cause RBC rupture in dogs. B. gibsoni is one of the small forms of Babesia spp. and is widespread around the rest of the world, including Australia1. Babesiosis in dogs can be caused by other Babesia spp., including large form Babesia – B. canis, B. vogeli and B. rossi, and small form Babesia – B. conradae and B. vulpes, all of which are exotic protozoal to New Zealand2.

B. gibsoni can be transmitted to dogs via ticks that carry infectious sporozoites in saliva. Haemophysalis longicornis (New Zealand cattle tick) is an endemic tick in New Zealand and is a known tick vector of B. gibsoni in Australia1. Rhipicephalus sanguineus (brown dog tick) is also a vector of Babesia spp. and is widespread around the world, including Australia but is not established in New Zealand3. Direct transmission is possible through B. gibsoni infected blood, such as blood transfusion, contaminated surgical instruments, and repeated use of the same needle. Direct transmission can also occur from bite wounds. Transplacental transmission has also been reported1.

Babesiosis caused by B. gibsoni is often mild and mostly subclinical, which makes detection of potential carriers difficult. Clinical signs vary depending on the immune response of the infected dogs. The most severe clinical outcomes (multiorgan failure and death) are typically seen in puppies and young dogs (<2 years of age)1. Chronic Babesiosis is manifested by intermittent fever, lethargy, and weight loss, and parasitaemia can persist for years. Acute Babesiosis can present with fever, lethargy, haemolytic anaemia, and marked thrombocytopaenia.

Regenerative haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopaenia are the most common abnormalities seen on routine blood tests. The anaemia is caused by mechanical damage to RBCs due to piroplasm migration out of the RBCs, intravascular haemolysis, and immune- or non-immune mediated destruction of RBCs. The mechanism of thrombocytopaenia has not been fully elucidated1.

In clinical veterinary practice, the most commonly used diagnostic method is microscopic detection of Babesia piroplasm on blood films. The blood film examination is easy to perform, faster than other laboratory tests (e.g. molecular and serology tests), and is economical. For detection of B. gibsoni piroplasms, a blood film made from a fresh blood sample is preferred, since degeneration of piroplasms can occur in stored blood. Therefore, submission of an EDTA sample with a fresh blood film (made in-clinic) is recommended when requesting haematologic examination at reference laboratories.

Unfortunately, automated haematology analysers are not helpful for detection of blood parasites, including Babesia spp. Thus, routine blood film examination is essential, particularly in cases where haematologic abnormalities are detected by automated haematology analysers.

No treatment providing complete elimination of B. gibsoni piroplasm has been reported, however the currently available treatment options may be helpful for improvement of clinical signs. Infected dogs frequently have disease recurrences even though they appear clinically normal and parasitaemia is no longer confirmed after treatment1. Thus, dogs recovering from an acute phase can become potential carriers of B. gibsoni.

For successful transmission of B. gibsoni to dogs, the ticks must suck into the skin for at least 48-72 hours1. Therefore, the use of repellent drugs for ticks is important for prevention of Babesiosis. Once attached ticks are found, the ticks should be removed as soon as possible. Also, situations in which dog bites/fights could occur should be avoided.

References

1. Karasova M, et. al. The Etiology, Incidence, Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, and Treatment of Canine Babesiosis Caused by Babesia gibsoni infection. Animals 12(6):739, 2022.

2. Biosecurity New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries. “Babesia gibsoni Information for veterinarians” April 2024.

3. Biosecurity New Zealand Ministry for Primary Industries. “Brown Dog Tick Information for Veterinarians” September 2023.