BERNIE VAATSTRA

Clinical history:

A two-year-old, domestic shorthair cat died on arrival at the veterinary clinic. The owner reported the cat had been unwell and produced brown, syrupy urine the previous day. Concern was raised about the possibility of malicious poisoning, since there had been a spate of suspicious cat deaths in the neighbourhood. The cat was sent to our Palmerston North laboratory for a post-mortem examination.

Post-mortem findings:

The cat weighed 2.6 kg and was judged to be in thin body condition and moderately dehydrated (sunken eyes, tacky subcutaneous tissues). Scant blood staining was present around the nares and mouth. The thorax contained brown, turbid, flocculent, foul-smelling exudate with flecks of yellow material (Figure 1).

The pleural surfaces and pericardium were thickened, red-brown and velvety. The lungs appeared collapsed but floated in formalin. No other significant abnormalities were detected on gross examination.

Fresh thoracic exudate was collected for culture and a smear was made for cytological examination. Tissues were collected for histology.

Laboratory findings:

Cytology of the pleural exudate revealed numerous degenerate neutrophils and phagocytic macrophages and fewer plasma cells, eosinophils and lymphocytes within a background of amorphous granular debris and numerous bacterial rods and filaments.

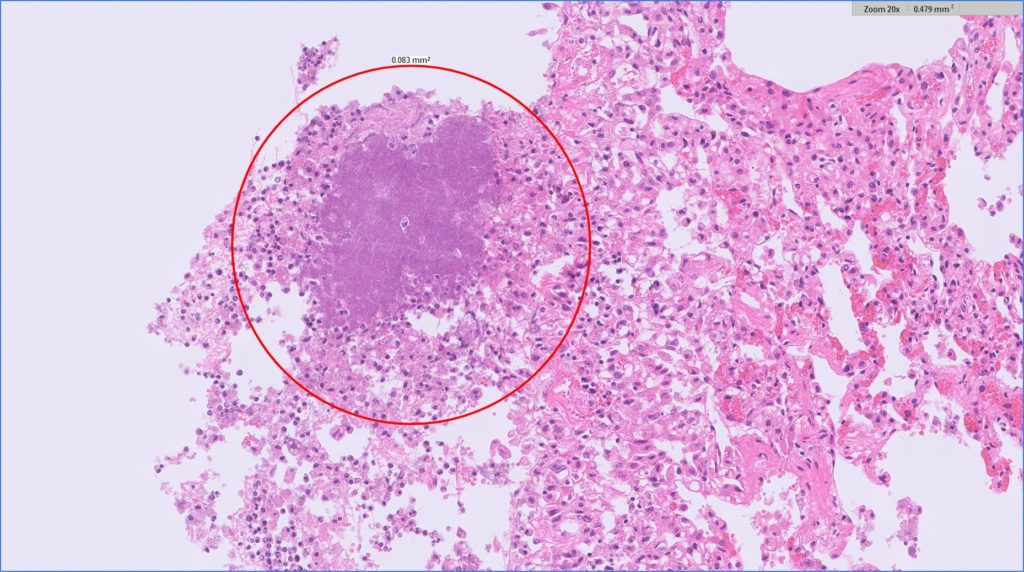

Histologically, the pleural surfaces were lined by thick layers of mixed inflammatory cells, fibrin, necrotic debris, and bacteria (Figure 2). Bacterial colonies were Gram-negative on Gram’s stain.

Culture produced a heavy growth of a Gram-negative organism, most closely resembling Bacteroides fragilis.

Discussion:

Pyothorax is a well-recognised, life-threatening condition in cats resulting from accumulation of septic exudate within the thoracic cavity. Clinical signs include dyspnoea, abnormal lung sounds, lethargy, and weight loss. The most prominent clinicopathological findings are leucocytosis and hyperglobulinaemia (Sim et al, 2021).

Bacterial isolates include Pasteurella multocida, E.coli, Streptococcus spp., Staphylococcus spp., and anaerobes such as Actinomyces, Nocardia, and Bacteroides spp.

The route of infection is not always identified but suggestions include thoracic penetrating injury (bite wounds), migrating foreign body, haematogenous and lymphatic spread, oesophageal rupture, and progression of inhalation pneumonia (Barrs et al, 2005).

Cats in multi-cat households are at increased risk.

Bacteroides species reside in normal feline oral cavities and in cats with gingivitis. One study reported Bacteroides spp. constituted 44.5% of the anaerobic isolates from subcutaneous abscesses and 33.7% from pyothorax cases (Love et al, 1989). Isolation of a heavy growth in this case, suggested a cat bite wound as the route of infection.

Many thanks to Mark Ross from Carevets Gisborne for submitting this interesting case.

References:

Barrs VR, Allan GS, Martin P, Beatty JA, Malik R. Feline pyothorax: a retrospective study of 27 cases in Australia. J Feline Med Surg. 7:211-22, 2005.

Love DN, Johnson JL, Moore LV. Bacteroides species from the oral cavity and oral-associated diseases of cats. Vet Microbiol. 19:275-81, 1989. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(89)90073-4. PMID: 2718354.

Sim JJ, Lau SF, Omar S, Watanabe M, Aslam MW. A Retrospective Study on Bacteriology, Clinicopathologic and Radiographic Features in 28 Cats Diagnosed with Pyothorax. Animals (Basel). 11:2286, 2021.