AREFEH RAVANBAKHSH

Mastocytemia refers to presence of mast cells in peripheral circulation. Mast cells originate from precursor cells produced in the bone marrow and following migration into peripheral tissue, they undergo further differentiation and maturation. Once in tissue they do not tend to recirculate and thus are not normally found in peripheral blood.1 The morphology of the mast cells and the species involved are important factors to consider when mastocytemia is detected.

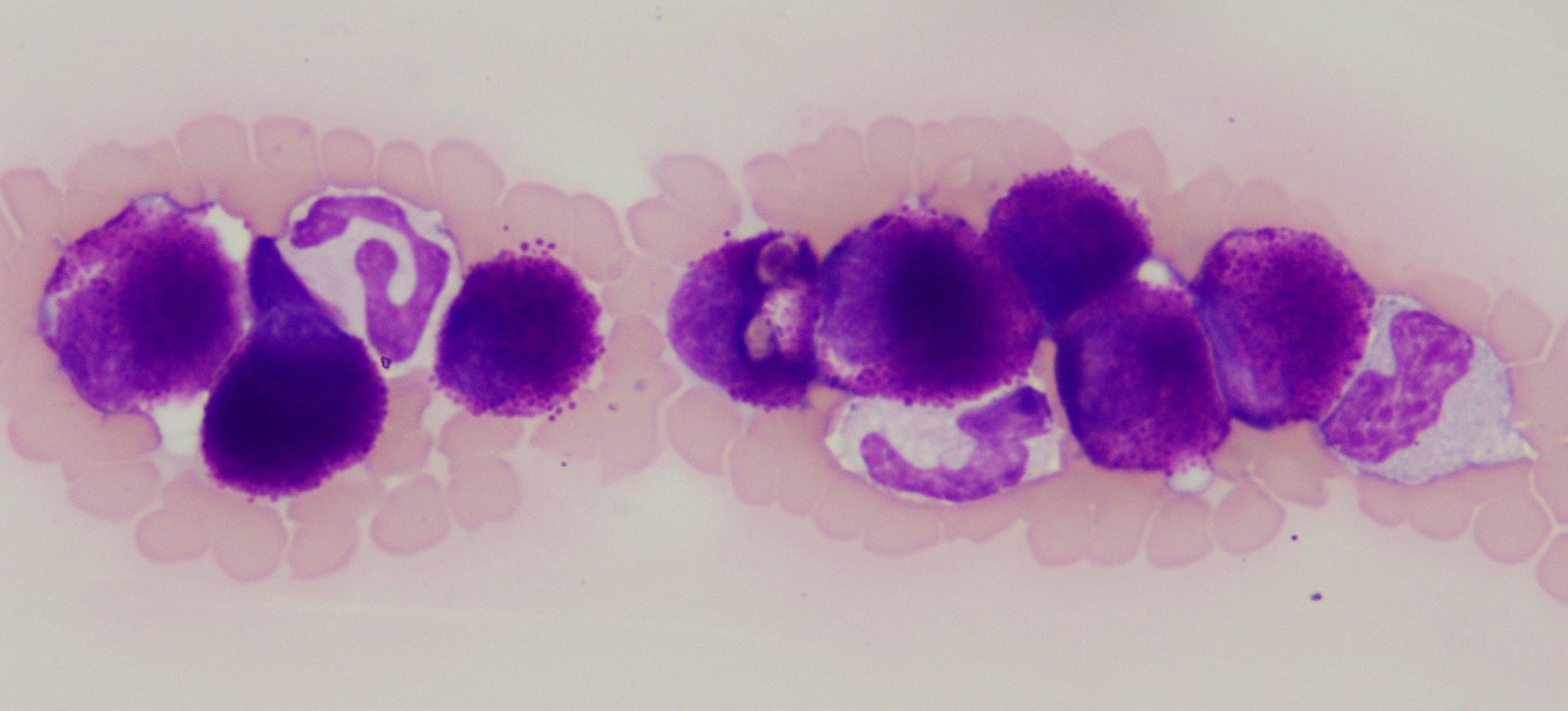

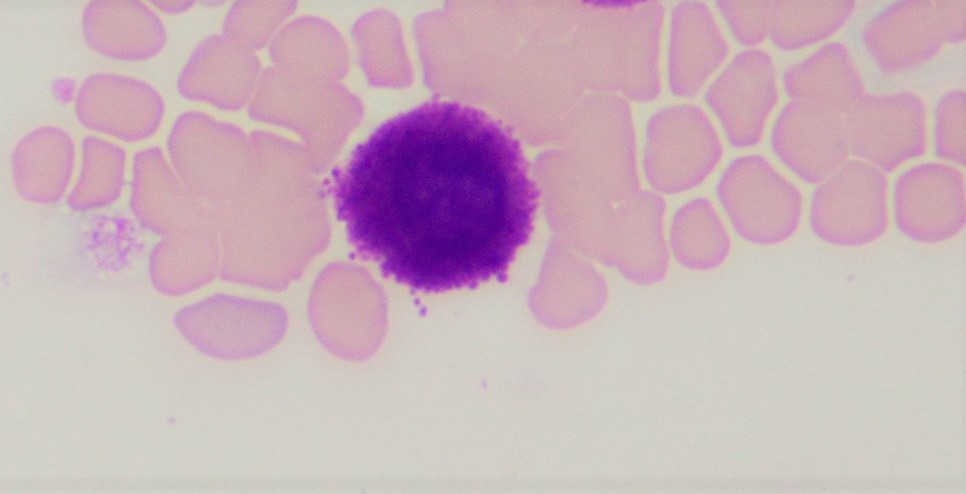

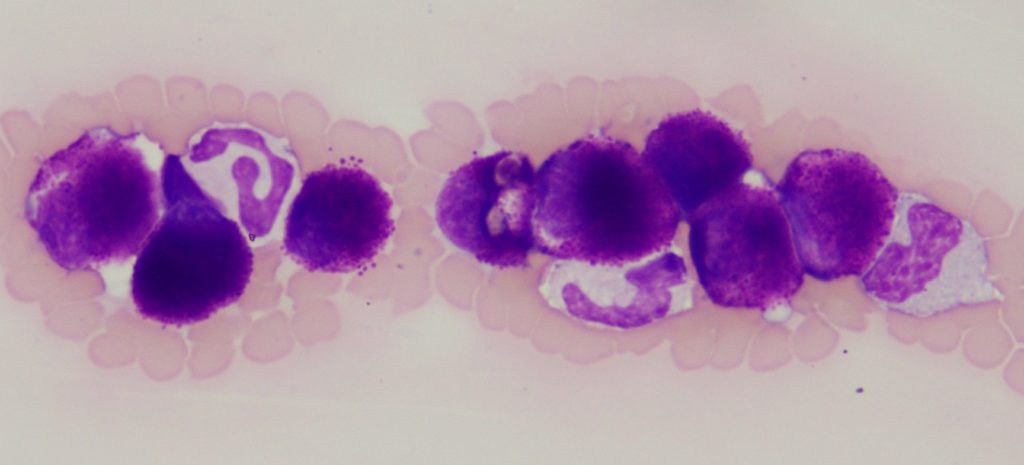

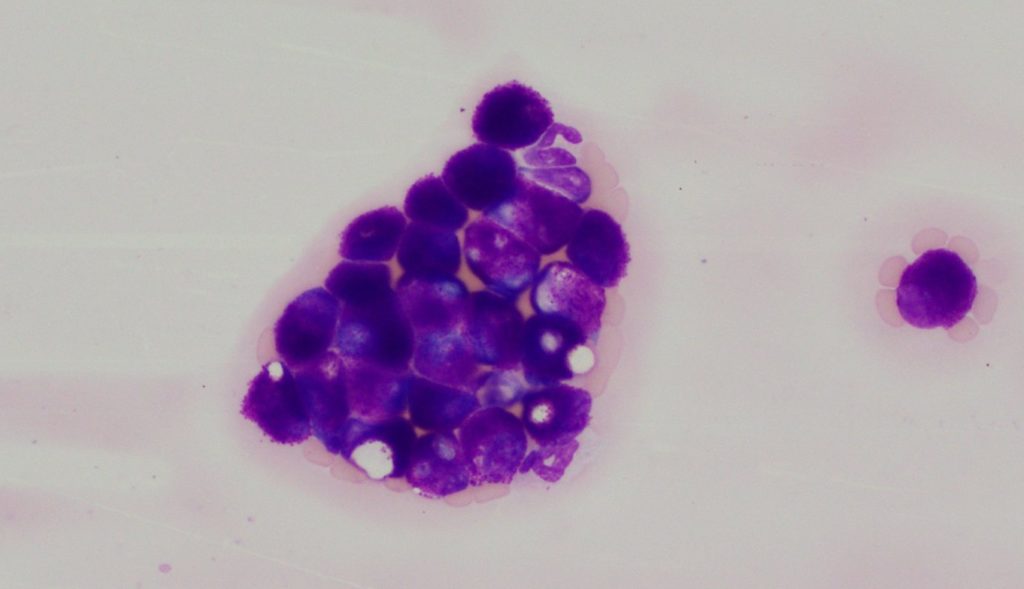

Well differentiated mast cells are round, have discrete cell borders, moderate amount of cytoplasm containing purple or metachromatic granules, a round to oval often centrally located nuclei, and usually indistinct nucleoli (Figure 1). Atypical mast cell morphology including prominent nucleoli, significant variation in nuclear and cells size, multinucleation, and irregular nuclear borders are suggestive of a neoplastic mast cell population.

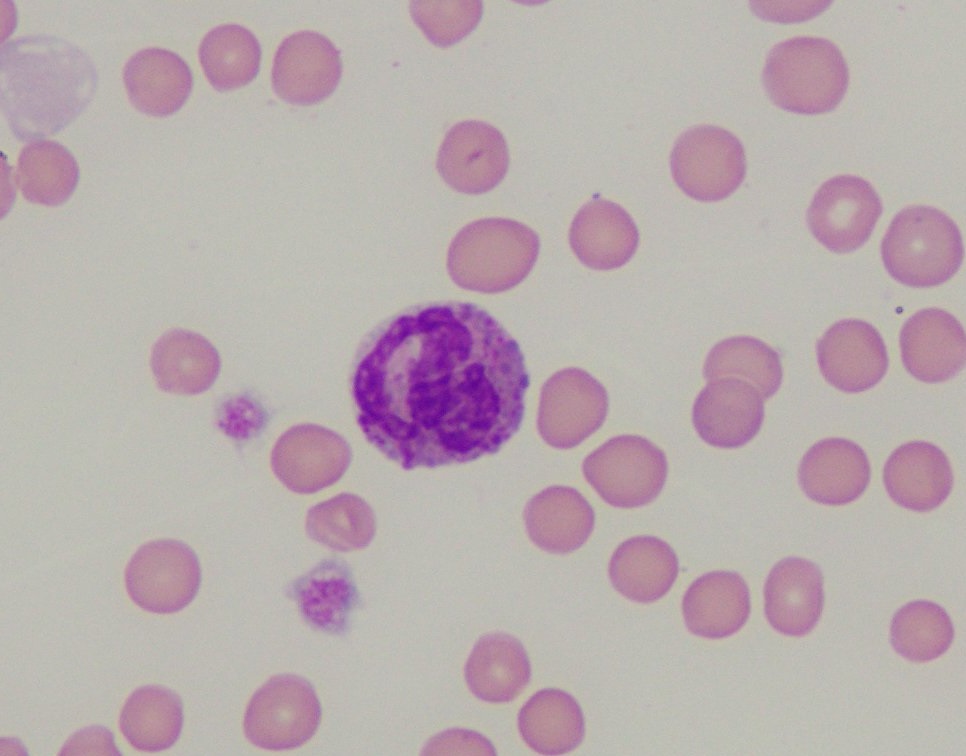

Mast cells can be differentiated from canine and feline basophils (a cousin of the mast cell), as the latter cells have segmented nuclei (stretched “ribbon like” appearance) and lavender to pale lavender granules (Figure 2).

Dogs vs cats:

In dogs, mastocytemia can be associated with a wide array of pathological processes including acute inflammation, disseminated mast cell neoplasia, severe regenerative anaemia, tissue injury or necrosis, non-mast cell neoplasia, and in rare cases myeloproliferative disease involving mast cell lineage.1,2,3 If clinical findings and clinical history are not supportive of a mast cell tumour and low number of mast cells are noted in the peripheral blood of a dog, look for signs of inflammation on the CBC (neutrophilia or neutropenia, left shift, and signs of toxic change) as inflammation is the most common condition associated with mastocytemia in the dog.1

Just like the albino alligator and the ti-liger (a mix between a tiger and a liger), detection of mast cells in the peripheral blood of cats is a rare finding. When detected, the vast majority of cases are associated with visceral mast cell tumours.1 In a previous study investigating the diagnostic and prognostic significance of mastocytemia in cats, a small percentage of cats with mastocytemia had clinical diagnosis other than a mast cell tumour, including lymphoproliferative disease and disseminated hemangiosarcoma.1 The authors also suggested that high numbers of mast cells noted in peripheral blood of cats is more likely to be associated with MCT than non-mast cell neoplasia.

Clinical signs of cats with visceral mast cell neoplasia can be varied and non-specific and include hyporexia, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhoea and lethargy. If mast cells are noted in peripheral blood of cats, even if organomegaly is not detected on physical exam, it is warranted to pursue additional diagnostics including imaging to look for mass lesions or evidence of organomegaly; and cytological or histopathological assessment of spleen and liver to investigate the possibility of mast cell neoplasia.

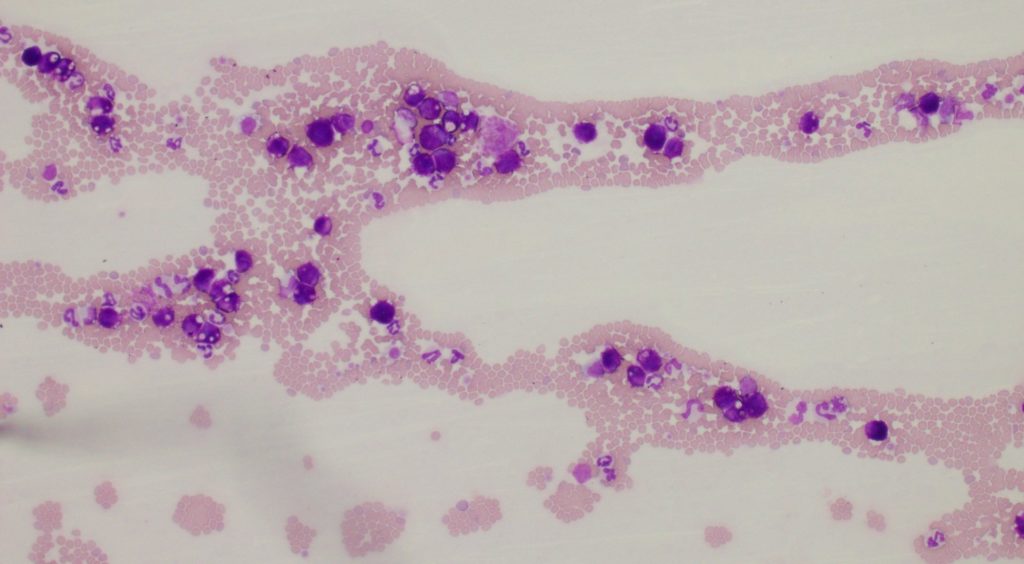

Mast cells are most often noted on the feather edge of a blood smear. A buffy coat examination can be performed to further aid in detecting mast cells in peripheral circulation. It is important to keep in mind that the lack of detection of mast cells on blood smear examination or buffy coat examination does not necessarily rule out mastocytemia, particularly in the cat.

In conclusion, mastocytemia is associated with a wide range of non-neoplastic and neoplastic conditions in the dog, while mastocytemia in cats is strongly associated with visceral mast cell neoplasia.

References:

1. Piviani M, Walton M, Patel R. Significance of mastocytemia in cats. Vet. Clin. Path. 41:1, 2013

2. Harvey J. Veterinary Hematology – A diagnostic Guide and Color Atlas. Pg. 152-153

3. Stockham S, Basel D, Schmidt D. Mastocytemia in dogs with acute inflammatory diseases. Vet. Clin. Path. 15:1, 1986