Arefeh Ravanbakhsh

Case history

A three-month-old intact female Staffordshire Bull Terrier was presented to the veterinarian for evaluation of multifocal areas of alopecia. Pruritus was not reported. Multiple skin scrapes of the affected areas were collected for cytological evaluation, and hair plucks collected for ringworm culture and potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation.

Cytological findings

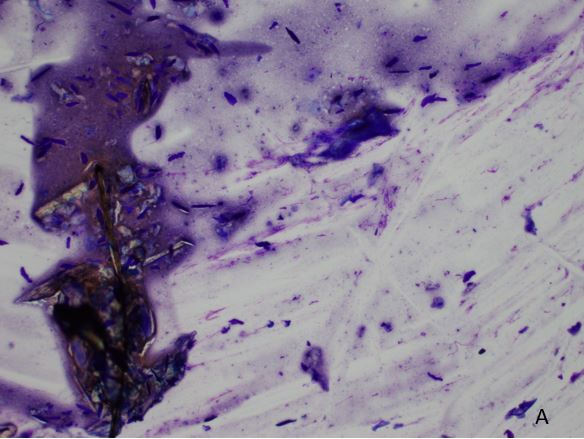

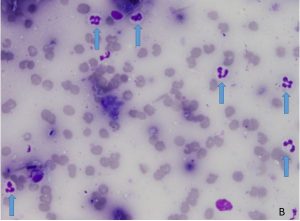

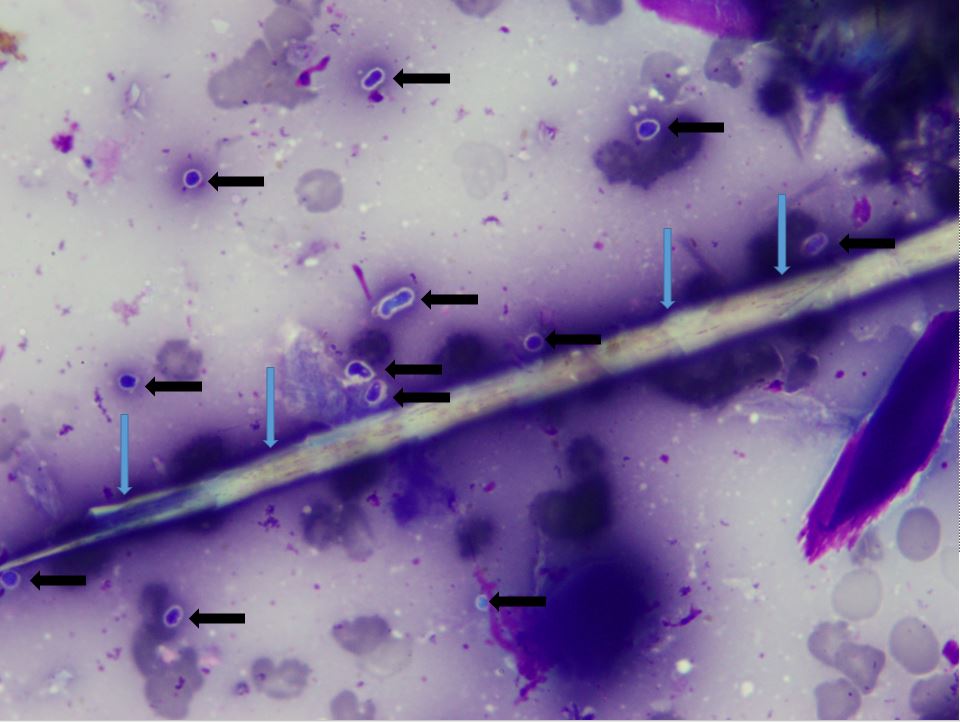

The skin scrapes were moderately cellular and of good diagnostic quality. The smears contained an abundance of superficial keratin and fragments of hair shafts on a mild to moderately hemodilute background (Figure 1A). Non-degenerate neutrophils were mildly increased compared to the degree of blood contamination (Figure 1B). Scattered in the background and occasionally associated with broken hair shafts were frequent small (2–4 micrometre) basophilic rounded-to-oval structures with surrounding thin, clear halos (Figure 2). Bacteria were not identified. The cytology interpretation was mild neutrophilic inflammation with presence of fungal arthrospores, most consistent with dermatophytosis.

Microscopy of the KOH preparation was positive for fungal spores and hyphae. Culture results came back as positive for Microsporum canis.

Discussion

Microsporum and Trichophyton species are the most common dermatophytes associated with ringworm infections in animals (Valenciano and Cowell, 2019). In cats, most cases are due to Microsporum canis infections. Transmission can occur via direct contact with an infected animal or contact with infected fomites. Dermatophytes have zoonotic potential. Anthroponosis is possible but uncommon (Caruso et al., 2002).

Animals most at risk of developing dermatophytosis include young animals (puppies and kittens), animals cohabitating in large groups, animals with underlying immunodeficiencies and animals under immunosuppressive therapy (Caruso et al., 2002). Other reported risk factors in cats include long-haired breeds and infestation with other ectoparasites (Caruso et al., 2002). A typical clinical presentation of dermatophytosis in dogs includes focal to multifocal areas of alopecia, crusting and papules (Logan et al., 2006). Less commonly, dermatophyte infection may present as focal or multifocal firm nodular lesions referred to as kerions. The lesions form when an infected hair follicle ruptures, releasing fungal organisms and keratin into the surrounding tissue and inciting a marked inflammatory response (Logan et al., 2006).

Cats with dermatophytosis can have more variable clinical presentations. Some are asymptomatic, while others may present with focal to multifocal areas of alopecia and crusting, often around the head, forelimbs and face. Lesions can also present as areas of broken hair shafts (Caruso et al., 2002). A less common presentation of dermatophytosis in the cat (grossly similar to a kerion) is a firm nodular lesion referred to as pseudomycetoma (Logan et al., 2006).

A cytological evaluation of an affected area can be an effective tool to provide support in diagnosing dermatophytosis with a relatively quick turnaround time. Skin scrapes can be collected by scraping in the direction of hair growth (Caruso et al., 2002). Collecting samples from the edge of active lesions is best for visualising fungal organisms (Valenciano and Cowell, 2020). The exfoliated material is then placed on a slide and allowed to air dry before staining. It is recommended that the scrape be deep enough to allow for some degree of haemorrhage, as blood and serum will aid in fixing the exfoliated material on the slide (Caruso et al., 2002). An additional advantage of performing skin scrape cytology is that it may allow for the identification of other co-infections (for example Demodex and concurrent bacterial infections). However, cytology cannot conclusively determine the species of fungal spores.

Aside from cytological evaluations of skin scrapes, there are multiple diagnostic tools that can be used to aid with the diagnosis of dermatophytosis. Wood’s lamp may be useful in some cases, although not all strains of dermatophyte fluoresce under a Wood’s lamp. Furthermore, some bacteria and chemicals can give false-positive results. A KOH preparation of infected hair follicles is another diagnostic tool with a relatively fast turnaround time, and it uses a KOH solution to clear the keratin from hair shafts to allow for better visualisation of fungal spores and hyphae (Logan et al., 2006).

The gold standard for a diagnosis of dermatophytosis is fungal culture; however, this test has a much longer turnaround time than the others (one to three weeks).

There are few options for collecting samples for fungal culture. It can be performed on hair plucked from affected areas, or a toothbrush can be used to comb hair gently onto paper. The toothbrush and the brushings can both be submitted for fungal culture. Although hair specimens are the more commonly collected samples for mycology culture, fresh biopsy samples can also be used. A histological evaluation of an affected lesion, with or without the use of a special stain, may be useful as well, particularly in nodular lesions. Histopathology can also aid in ruling out other neoplastic and inflammatory conditions that may mimic dermatophytosis clinically.

In conclusion, skin scrape cytology can be a good tool in the diagnosis of ringworm in animals. Its quick turnaround time is an advantage when it is used to provide support for suspected dermatophytosis cases, and this in turn allows for a quicker initiation of therapy and reduces the chance of contagion. Ideally, it should be used in conjunction with fungal culture in suspected dermatophytosis cases.

References

> Caruso KJ, Cowell RL, Cowell AK, Meinkoth JH. Skin scraping from a cat. Veterinary Clinical Pathology 13, 13–15, 2002

> Logan MR, Raskin RE, Thompson S. ‘Carry-on’ dermal baggage: A nodule from a dog. Veterinary Clinical Pathology 35, 329–31, 2006

> Valenciano AC, Cowell RL. Cowell and Tyler’s Diagnostic Cytology and Hematology of the Dog and Cat. 5th Edtn. Elsevier Saint Louis, Missouri, USA, 2019