Wilson Karalus

Clinical history

A three-year-old dairy cow presented for severe ulceration of the dental pad and hard palate, towards the back of her mouth near the base of the tongue (Figure 1). Hypersalivation was noted and she had evidence of ulceration of both nostrils, with clear nasal discharge and enlargement of the mandibular lymph nodes. There were no other lesions present, however she was lethargic with a decrease in milk production. No evidence of pyrexia was noted. She was vaccinated for bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) when young.

Figure 1. Ulceration of the hard palate towards the back of the oral cavity.

MPI were contacted to investigate the case due to the possibility of exotic disease. The duty incursion investigator was able to exclude vesicular disease based on epidemiological and clinical findings, and an endemic cause for these unusual lesions was sought.

Laboratory testing

Serum was collected and testing for BVD and malignant catarrhal fever (MCF) were both negative. A biopsy of the area was then collected and submitted to Awanui for processing and analysis. MPI paid for all laboratory testing as part of the usual exotic disease investigation process.

Histology findings

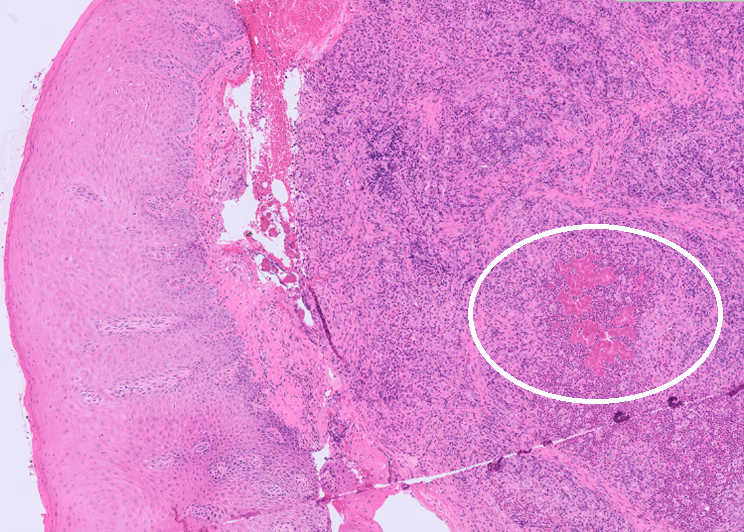

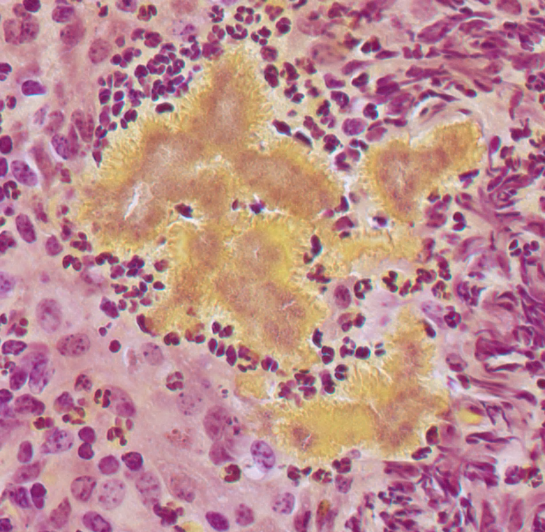

Within the submucosa of the oral cavity were large colonies of Gram-negative bacteria surrounded by bright eosinophilic hyalinized material forming radiating, club like projections (Splendore-Hoeppli material) (Figure 2). These were surrounded by large numbers of neutrophils, which were further surrounded by dense aggregates of macrophages, with fewer lymphocytes, and plasma cells. The overlying oral mucosa was intact, with no evidence of pustule, or vesicle formation.

Figure 2. Within the submucosa of the oral cavity are nodules of pyogranulomatous inflammation surrounding, brightly eosinophilic Splendore-Hoeppli material (circle), H&E 20x (left). Within the material, there are Gram-negative colonies of bacteria, Gram-stain 40x (right).

Diagnosis

The presence of Gram-negative bacteria surrounded by Splendore-Hoeppli is almost pathognomonic for Actinobacillus lignieresii the agent responsible for Woody tongue in cattle.

Discussion

The combination of oral ulceration, with classical microscopic appearance is compatible with an uncommon presentation of oral actinobacillosis (woody tongue) due to infection with Actinobacillus lignieresii. This bacterium is part of the normal oral and rumen flora of cattle and trauma to the tongue, or oral mucosa through ingestion of rough plants/forage, or through teeth abrasions is thought to be the primary route of infection. Most clinicians will be familiar with ‘woody tongue’ in its typical form, where it leads to a very firm, hard, tongue, with clinical signs of drooling, loss of production, and lethargy (Uzal., et al 2016). However, a more uncommon presentation can occur, where oral ulcers are seen as the main lesion. Other reported sites include the involvement of the parotid, retropharyngeal, mandibular, and occasionally more distant lymph nodes (Caffarena., et al 2018). Infection may also extend into the overlying skin which becomes ulcerated and forms draining lesions. Other even less common sites include the oesophagus, lung, and peritoneum, as well as the walls of the forestomachs (Kasuya., et al 2017).

Actinobacillosis can be treated with broad spectrum antibiotics, with streptomycin the preferred antibiotic. Due to the issue of withholding periods when using antibiotics, another commonly used treatment includes sodium and potassium iodide. These treatments are also less costly than antibiotics, another reason for their employment. Sodium iodide can be given intravenously, and often only requires one dose, at 1g/12kg live weight as a 10% aqueous solution to produce resolution of clinical signs. Follow up doses can be given at 7 and 14 days if required (Parkinson., et al 2010). However, if repeated doses are used then the cow must be monitored for signs of iodine toxicity. Potassium iodide can be given orally at 6-10 g/day for 7-10 days, while again monitoring for signs of toxicity. Clinical evidence of iodine toxicity includes the appearance of dandruff, along with anorexia and coughing. The prognosis is generally good following treatment and signs of improvement are usually seen within 48 hours of treatment (Parkinson., et al 2010).

Differentials for typical actinobacillosis include Actinomyces bovis the causative agent of ‘lumpy jaw’, or other less common bacterial infections including Nocardia spp. and Staphylococcus aureus (Botryomycosis). However, the differential list for this case was slightly different due to the presentation. In New Zealand, the main differentials for oral ulceration include BVD, MCF, and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR). Other important differentials to always keep in the back of our minds include exotic diseases such as foot and mouth disease, and vesicular stomatitis. This case highlights the importance of keeping these exotic diseases on our minds, and contacting MPI whenever we have a possible exotic disease presented to us.

Acknowledgements to Dr. Murray, Franklin Vets, and Dr. Taylor, MPI for this case.

References

· Caffarena RD et al. Natural lymphatic (“atypical”) actinobacillosis in cattle caused by Actinobacillus lignieresii. J Vet Diag Invest. 30:218-225, 2018.

· Kasuya K et al. Multifocal suppurative granuloma caused by Actinobacillus lignieresii in the peritoneum of a beef steer. J Vet Med Sci. 79:65-67, 2017.

· Parkinson TJ, Vermunt JJ, & Malmo J. Diseases of cattle in Australasia: a comprehensive textbook. New Zealand Veterinary Association Foundation for Continuing Education. 2010.

· Uzal F, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals, 6th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier, 2016.